Entering Others’ Stories: A Spoiler-Free Recommendation of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen

I enjoy books that let me enter into someone else’s experience. I always have. I don’t see how anyone who grows up reading could become a bigot.

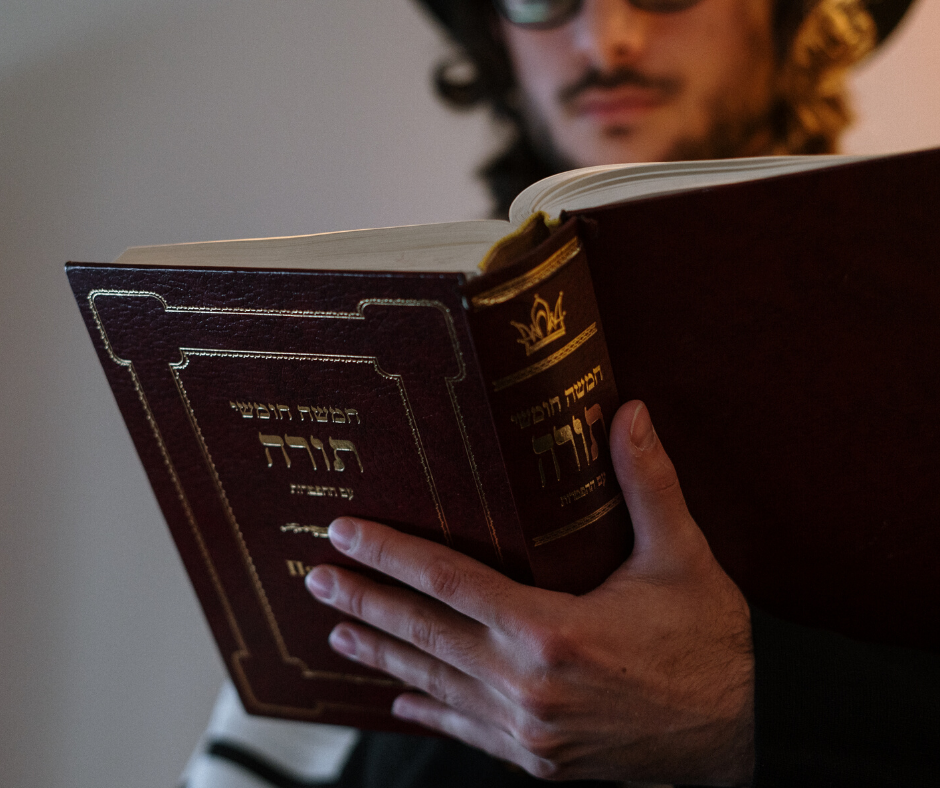

My most recent finished read was Chaim Potok’s The Chosen. Set in the Jewish community of Brooklyn during World War 2 and its aftermath, the book takes the reader into the life of a typical young Orthodox Jew of the time. The first personal change the war brought Reuven Malter was baseball. In a country gone to war, what better way for the Orthodox to prove the physical fitness of their young men – young men who spent hours every day studying first their religious texts, then several more hours on subjects typical to other American students – than for them to form their own competitive sports leagues.

Reuven’s first encounter with Danny Saunders was on the ball field. It was brutal.

Danny wasn’t merely of a strict Hasiddic sect, he was the son of a tzaddik. Like what we think of as the usual rabbi, Danny’s father was a spiritual leader and teacher. But as tzaddik, he was considered righteous by his followers. He was the unquestioned authority, as his father before him. For generations leadership had passed from father to son. For tzaddiks who led like Danny’s father, the cost was steep. As tzaddik, he led alone. As his followers visited him one after the other with their pain, he accepted the weight onto his shoulders. He took up the burden of all Jews’ suffering. He believed it was his duty as tzaddik to carry every weight placed on him, which was every weight he was aware of in the world, a world at war, a world where Jews were persecuted and slaughtered. Alone.

The price for the son: silence from the father. Except when they were discussing the Talmud.

There were several Hasiddic sects in the predominantly Jewish neighborhood, typically occupying a particular block. They were not only distinct from the larger Orthodox community, but also from each other by their attire, customs and separate synagogues. Reuven recognized the characteristic attire of Danny’s Russian Hasidic Jews, and knew some of their customs, as he recognized the sect from southern Poland another block down. He didn’t seem to know exactly how many distinct ethnic sects there were within the Hasidic sect of the Orothodox Jews in Brooklyn.

Something all the Orthodox families had in common was that every boy attended a yeshiva, a Jewish parochial school, where the dominant subject was the Torah. When Danny’s and Reuven’s teams were finally brought together in competition, Danny’s came in with a clear belief in their superiority to Reuven’s. After all, Reuven and his friends weren’t Hasids. They committed the sacrilege of studying the Torah in the holy Hebrew instead of Yiddish. Their yeshiva provided more than the minimum required English courses..

The Hasidic team came in with victory their only option. When winning came down to it where it cost, Reuven was the only member of his team fully committed to resisting defeat.

And it did cost him.

But it also brought a previously impossible experience of great value.

An early lesson in the book is that an enemy can become a friend.

The Chosen reminds readers that within every group there are differences, and they can be vast, however they appear to those outside. In writing about our current events, my and others’ thoughts and feelings surrounding the murder of George Floyd and its ongoing aftermath, positive and negative (the writing still unfinished, by the way, becasue it always spins beyond my control), I was at one point trying to make this point.

Whenever we lump any particular group together under particular assumptions, we’re at risk. We miss the individual.

I’m a woman. I live in a rural area. I live in an economically depressed county, in a predominantly white region. I’m white. My boyfriend in 1998 and ‘99 was black. I was raised in a financially-disadvantaged household. I’m a writer. I’m a waitress, at a buffet restaurant. I work in a library. I’m college-educated. My degree is in psychology. I’ve worked in the public school system. I was on the board of a private Christian school. I’m a Christian. I’m a registered Republican. I’m from New York State. I’m pro-life. I’m a mom. For almost a decade I’ve been treated for mental illness, bipolar 2… which means I’m mentally ill. I’m 47.

There are various assumptions people might make about me based on any of these parts of who I am, and my various roles. Many of these assumptions are at odds with other assumptions, generalities, and stereotypes attached to various demographics I am categorized in, and cultures and subcultures I’m part of. Some of them fit. Some of them don’t. Some I flat-out reject.

No one fits neatly in any box.

Be open to others’ stories. The ones that do and don’t fit your chosen narrative. Treat everyone with their God-given dignity. Don’t let anyone browbeat or shame you out of your beliefs or acceptance of your worth, but, at the same time, be humble and teachable. We are none of us perfect. And we are all ignorant of many things.

Because we’re human.

Disclaimer: If you click a link and make a purchase, I will receive a small commission as an Amazon associate. This will not affect your cost, but helps defray the costs of keeping my blog up and running. Thanks!