The Water Is Where

Her breath fogged the glass. But what did it matter? The landscape was as dull and colorless as the clouded pane. A sunless January thaw. Crisp white snowdrifts softened and sodden. The world sagged like the flesh on her cheeks, along her jaw, around her eyes.

She didn’t move away from the window, but leaned her head against the frame.

Lydia had always disliked the bareness of a home after the holidays, how houses looked so empty after the Christmas decorations were packed away. Stark. She should have gotten used to it by now, in the two weeks since the annual post-New-Year’s-Day purge of baubles and lights, tinsel and evergreen. But the bereft cottage, that had seemed quite cozy as the autumn chill settled in, was an even less appealing view than the landscape.

Well, Lydia, lonely is what you end up when you decide to divorce your husband as your flock leaves the nest. She could always count on her mother for disappointment and disapproval, even if their holiday celebration had been blessedly limited to video calls over hundreds of miles.

But it wasn’t that. She didn’t miss her ex. She’d assumed at some point she’d miss having someone to come home to, someone who came home to her, a warm body, day-to-day conversations about everything and nothing, but she hadn’t reached it yet. Leaving Greg was the best choice she’d made in a long time. She’d relished the peace, though the price had been steep. She certainly wasn’t lonely for her mother, and she’d never had a father to miss. Though every fatherless girl at some point yearns for that presence in her life, Lydia was no longer a girl, far from it. She’d missed her kids’ holiday visits from their various places around the country, but it wasn’t as hard as she’d expected, the exceptional COVID Christmas. Distance and busyness, the divorce and sale of the house, had already altered how they did family.

She wasn’t lonely.

But what was she?

Lydia raised her head, and looked out over her shrouded lawn, down the hill, across the field, to the lake. It wasn’t like Ontario where she’d spent part of every childhood summer with her grandmother, and every winter and spring break. This was small and calm, its ice smooth and skateable, not thrown up in massive chunks along the shore, there one morning after a storm, maybe gone the next. Jagged and dangerous as the waves pulled in and out beneath them, spewing frigid volcanoes toward the sky.

There would never be anything like that on Gower’s Pond, but it met the definition of a lake. She’d Googled the difference. It was, in depth and breadth, a lake. As the Greats were inland seas.

“Stay back,” her aunt always warned. Like she could feel the heat of her niece’s fascination through the cold air. Was it true Aunt Til had let it take her one winter day Lydia was away at college? Or had she just failed to follow her own advice to stay back, at least just far enough, beyond the reach of the boldest waves that shift the surface as they strive for the buried shore. It would have taken just one. One wave. One shift. One misstep. One slip. One last breath finding air. Did she fight that next inhalation, until her lungs were screaming and could wait no longer? Or did she just slip away, realizing she’d known all along this was the cold embrace she’d end in?

Lydia had always wondered.

She shook her head to dislodge the dark.

So long ago. A lifetime. Lifetimes. Lydia’s. Then her children’s, launched in almost every direction. South. West. North; she hadn’t seen that one coming. You couldn’t get much further east than where they’d all started in Central New York—closer to Canada than New York City; more cows than cabs she’d explained to Greg when they’d met all those vanished years ago… it’s funny what you think of—but she herself had done it, in New Hampshire, far from Lake Ontario.

But water is water, isn’t it? And the water is where she always found herself.

Jacket. Snow pants to resist the melt. Boots. Toque because her ears always got cold. She sat down on the back step to strap on her snowshoes.

The worst time of year. No color. Sky too dull to be white, too washed out to be gray. The bare trees weren’t quite black. Too little sunlight for the evergreens to the east to live up to their name. And the lake. A smudge. Darkening and rotten to the open water at its heart.

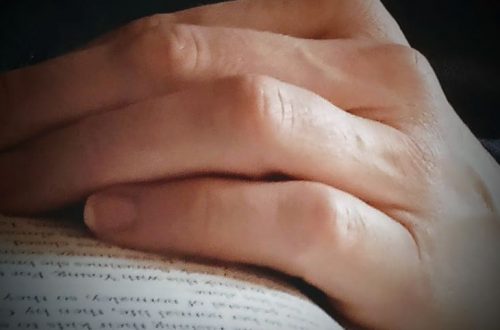

It took longer to get there than she’d expected, but she stood at the edge sooner, too. Isn’t life like that? Childhoods. Careers. Marriages. The monotony of a million moments that stretch on endlessly until suddenly you reach a border you’d lost sight of, and teeter. Which way to step? Pain always lasts too long; pleasure gone like a breath exhaled. And youth? Well, some things you reach the end of without noticing until you look around and realize you’ve gotten yourself somewhere that foreign has entered your familiar. Like the wrinkles on her hands struggling with the straps of her snowshoes.

Her feet freed, she jammed the snowshoes into the wilted remains of a drift. One fell immediately. The second slowly listed, then slid to the ground with a whispery shush. The skin between her boot-tops and knees was clammy with damp that had already seeped through her layers.

Lydia looked out over the ice and slush and water, and remembered something that used to mean something: she was the only one who would ever, could ever, see the view exactly as it was. The view, the moment, hers alone. But the landscape was empty. The moment graceless. And she could stand there the rest of the day and nothing would change until the watery light was overtaken by sullen dark.

The ice had no crunch when she stepped out, away from shore and shallows.

Light can reach the bottom of a pond.

Had it followed her all these years? This… nothing… that had swallowed her unplanned and unintended gap year that turned into two. She survived. Went back to school. Reentered life. And forgot how badly numb hurt.

Had she carried it, in fitful sleep somewhere deep inside, waiting to reawaken when she wasn’t too busy with life to notice?

Maybe it had waited for her here, out beyond the ice in embittered water. Biding its time until she found her way. Reaching for her in the cottage she could never have imagined she’d end up in, especially alone.

She took another step. And another. The ache in her chest easing the farther she got from the empty shore.

The ice trembled.

It’s true, she realized. There’s relief when the choice is made. Knowing she’d no longer have to live under the weight of will I or won’t I she’d been unaware of carrying. The pain could end; the pain would end.

Another step.

A shudder.

Another step.

A splintering.

She smiled. Just a little.

Then it all came apart.

Shattered by an unexpected sound.

There on the far shore, a manically barking dog, jumping and pacing. A flash of red bobbing down between the trees behind it.

No.

No, no, no, no.

She turned away. Hoping to avoid the stranger noticing her out there on the caving ice, waving her off. Hoping to save the dog from rushing out to save her…

Hoping?

Hope…

Stripped of feathers years ago, it had found her once again.

She swallowed her scream—the rage, resentment, pain as the peace of the brink was torn away—and made her way back up the hill, away from the saviors that drove her from salvation, resigned to the burden that weighted her feet to solid ground.

Read about the writing of this story here.

This story originally appeared on Vocal.media